How can we achieve progress in girls’ education? Why toilets alone aren’t enough…

Improving WASH facilities is a step in the right direction, but this needs to be coupled with knowledge-sharing and commitment.

-

Date

March 2024

-

Areas of expertiseEducation , Cross-cutting themes

-

CountryUganda

-

KeywordsWater sanitation and hygiene (WASH) , Girls' education

-

OfficeOPM United Kingdom

One in every three school children, or around 539 million school children globally, does not have access to a functional toilet in their schools. Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) is important to people’s multidimensional wellbeing, including in education, health, climate resilience, employment and more. For governments with limited budgets, it also makes financial sense to invest in WASH infrastructure, maintenance and knowledge. As a recent study across four countries (Ecuador, India, Nigeria, Philippines) found, the economic and societal costs of neglected school toilets—defined as toilet loss—was about $1.9 billion. That is a $1 loss for every $5 invested in school toilets.

Reinforcing gender divisions

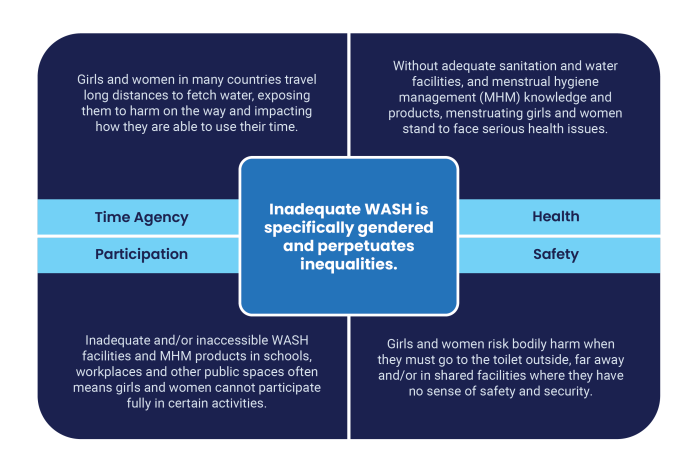

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 aims for equitable, universal and sustainable access to WASH by 2030. But safe, accessible and equitable WASH is a distant reality for billions across the world, especially in low-income countries. Inadequate WASH is also specifically gendered and perpetuates inequalities. The figure below illustrates some examples of gendered inequalities that can be perpetuated and/or created when WASH facilities are not accessible and/or inadequate, leading to issues around safety, participation, health and time agency among others.

Truly inclusive

Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) is especially key to an inclusive approach to WASH programming. Beyond simply the availability of safe and functional WASH infrastructure, which is critical for adequate MHM, school-age menstruating girls throughout the world are navigating social norms, taboos and culturally rooted practices and beliefs that often systematically exclude them from school. Promoting appropriate MHM knowledge and practices does not only make sense for sanitation and hygiene; it is also important for improving well-being outcomes for girls’ education and other human development outcomes.

We recently completed a three-year impact evaluation of a WASH programme implemented across a sample of government schools in Uganda. The programme focused on: the construction of WASH facilities; WASH promotion activities in schools; and MHM. The findings revealed key insights on numerous and interlinked components for successful WASH programmes in schools, some of which are shared below:

- A dual approach: Access to improved and functional WASH and MHM infrastructure, combined with promotion activities around handwashing, hygiene and menstrual health – for example, in school ‘health clubs’– can lead to improved WASH and MHM practices. This is facilitated by programmes that use a dual approach, combining both the physical WASH infrastructure—the hardware—and several knowledge-sharing and knowledge-building activities on WASH and MHM—the software—to promote WASH and MHM.

- Building capacity: The status, reliability and functionality of toilets and drinking water infrastructure matters for sustainable WASH practices. We found it was critical to build the capacity of school management personnel to develop and manage budgets for the timely maintenance of school WASH facilities. Furthermore, the broader community’s participation in the upkeep of a school’s WASH facilities, which can often be accessed by the local community’s members, is also key to the long-term sustainability of the WASH facilities.

- No ‘one-size fits all’: Accessibility and safety of WASH infrastructure is particularly important for girls and pupils with disabilities. Without an accessible toilet, disabled pupils will likely avoid school, especially if they do not have someone at school to support them with toilet use. Toilets that cannot be locked carry safety and privacy concerns, especially for menstruating girls. The provision of separate toilets—such that girls, boys and the disabled do not share the same toilets—is important to reduce congestion and breakdown of toilets while also improving access for the different groups.

- Context-specific: Appropriate MHM practices rely on adequate knowledge of MHM, access to suitable WASH facilities and access to MHM products and safe disposal methods. Girls’ school attendance during menstruation is often contingent on their access to sanitary pads while at school, and even spare uniforms or clothes. The uptake of appropriate disposal of sanitary pads, such as through incinerators, is more likely where interventions also combine knowledge-promotion activities. Knowledge promotion needs to include both the methods of disposal—such as burning or burying, rather than throwing into latrines and likely causing blockages—as well as address potential cultural and behavioural barriers, rooted in a contextual understanding of existing practices, attitudes and taboos.

Making it meaningful

The programme confirmed what several others have found before us, that education outcomes improved for girls—through higher school enrolment and attendance—where WASH and MHM were accessible and adequate. Learning from our approach, we are positive that scaling up inclusive programmes that incorporate both WASH and MHM components can elevate education equality locally and globally. But successful scale-up is more likely where there is: access to key WASH and MHM infrastructure and resources; local capacity building; area-wide implementation enabled through the existing education and/or health systems; strong buy-in from governments; and local community involvement and commitment. While coupling MHM with WASH is not new, finding cost-effective ways to scale and sustain such interventions by working across sectors remains key to helping girls stay in school longer, especially in communities where girls drop out of school upon reaching puberty due to social and WASH factors.

Photo by: Sarvdeep Singh Arora for OPM