Climate change loss and damage: Can sovereign insurance play a role?

Learnings from an evaluation of the African Risk Capacity

-

Date

December 2022

-

Areas of expertiseClimate, Energy, and Nature , Research and Evidence (R&E)

-

KeywordsClimate policy and finance , Disaster risk , Shock response , Data collection , Evidence use , Impact evaluation , Quantitative methods , Research uptake , Value for Money (VFM) , Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) , Quantitative impact evaluations (QIE) , Quasi-experimental , Randomised Control Trials (RCTs)

-

ProjectIndependent evaluation of the African Risk Capacity

With climate change, the frequency and severity of disasters globally – and drought in Africa specifically – are intensifying. The poorest and most vulnerable are often the worst affected. COP27 made a huge breakthrough in agreeing to set up new funding arrangements to support developing countries and their citizens to cope with the effects of the climate crisis.

While the new Loss and Damage Fund – agreed to both surprise and relief at COP27 – exists currently only on paper, considerable financial commitments were made to the Global Shield Against Climate Risks – a predominantly insurance-based initiative announced at COP27 by G7 and V20 countries.

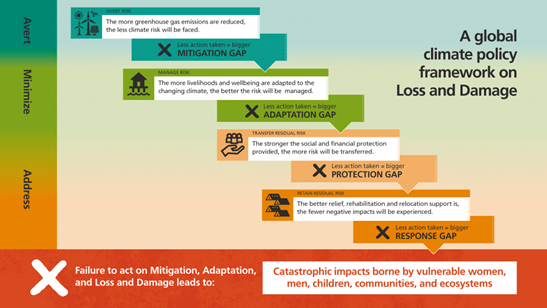

There have been mixed views on insurance within the UNFCCC process for many years. While insurance has an important role in helping to close the ‘protection gap’ (see Figure, below), it can only cover a small part of loss and damage. It cannot address non-economic aspects such as losses of life, damage to cultural heritage and ecosystems, slow onset events such as sea-level rise, or frequent hazards.

Source: Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance

Moreover, micro-insurance is usually not the best solution for the poorest people, who have many risks, little income, and few assets to insure. But is there a broader role for sovereign insurance – that is, insurance purchased by national governments – in helping to reduce the impact of drought and other climate-related disasters on the poorest?

We recently undertook our second formative evaluation of the African Risk Capacity (ARC), a specialised agency of the African Union, which builds capacity in member countries to respond to climate disasters and provides them with risk transfer services in the form of insurance. In the event of such disasters, insurance payouts are intended to reach recipients more quickly than conventional humanitarian responses. We identified three key issues that affect how relevant this support is.

First, it is important to be clear what role this insurance should play - and for whom. The overall level of demand and need for sovereign risk pooling is unclear – countries, particularly those in Africa, may be unwilling to purchase such insurance without donor subsidy, and payouts are often small relative to government budgets and the size of the disaster funding required. So would this be an appropriate use of donor resources? Part of ARC’s role may be, in fact, to provide ‘institutional fixes’ to challenges in financial allocation within governments and in the international humanitarian response, particularly in support of early responses. Strengthening sovereign leadership and national government capacity to respond are also important objectives. Since there are alternative mechanisms for meeting all of these objectives, ARC and its key stakeholders must clarify its core ‘value proposition’.

Second, African governments need the capacity to ensure that ARC payouts can be converted swiftly and efficiently into support to those people most in need. Our evaluation found that ARC has strengthened capacity to respond to drought through contingency planning and insurance in 17 out of 35 member states. Its support is widely valued by recipients.

‘We are managing to do the [drought risk model] customisation and understand our risk. ARC has been eye-opening – helped us to plan in advance.’ Country respondent

However, the distribution of support to beneficiary households by governments that received a payout often did not happen within four months (the mandated time period), undermining ARC’s main objective of a swift response. In addition, Government targeting processes were not consistently ensuring that the aid reached the people most in need.

Finally, these mechanisms require an effective institutional framework and predictable financing. ARC’s drought insurance risk pool has grown considerably in recent years - due in a large part to subsidies on insurance premiums and a programme of parallel insurance for NGO networks. However, ARC is currently facing a potential financing crisis. It also faces a number of organisational challenges including the division of roles between its two component organisations and a need to manage costs and improve reporting. These issues will need to be addressed if ARC is to be part of Africa’s long-term response to climate change.

While there is clear potential for ARC insurance to support drought response in Africa, after eight years of operation there remain questions over whether this potential is being achieved in practice.

African institutions should be central to reducing the impacts of climate change in Africa. Policy makers should identify what role they see for sovereign insurance, what they expect from ARC and how they can ensure the mechanisms are in place to rapidly and effectively distribute aid financed by it.

About the authors:

Patrick Ward is Technical Director for Evidence and Evaluation with more than 20 years' experience in monitoring and evaluating social sector programmes, including those in health, education, social protection and nutrition.

Debbie Hillier now leads Mercy Corps' work on flood resilience but this blog reflects work undertaken whilst she was Principal Consultant at OPM and a key contributor to the evaluation.